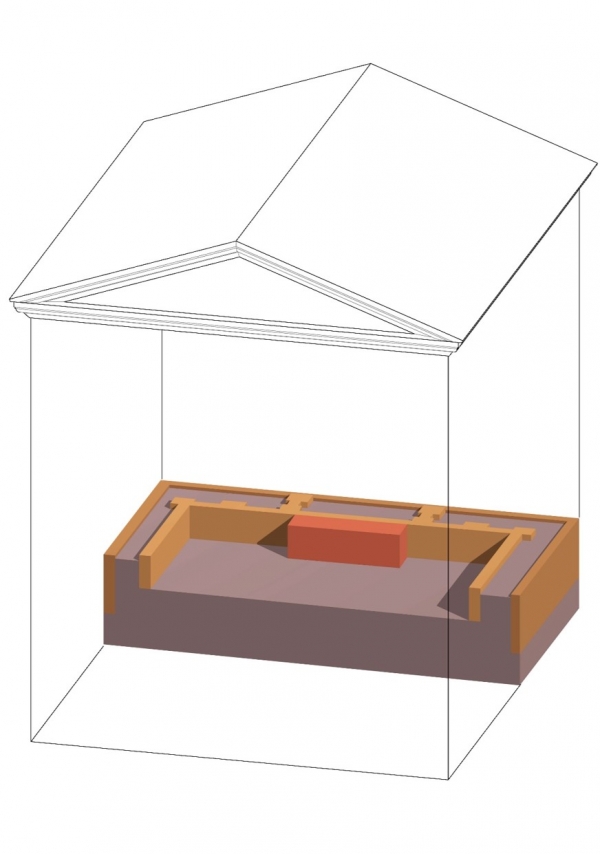

The Curia of Pompey was one of the great meeting rooms of profound historical importance during the Roman Republic. Located on the eastern flank of the ancient Portico of Pompey, within its walls the senators of ancient Rome discussed weighty political affairs in private meetings.

What is now a visible site for pedestrians who circulate through the Roman square of Largo Argentina, was actually constructed in several phases, ranging from the time of Pompey himself to the medieval era. This is, at least, what has been corroborated by a study carried out by an Italian/Spanish research team on which the University of Córdoba participated.

This fact had already been ascertained by stratigraphic studies carried out by the Spanish team that worked on the site between 2013 and 2017. Now these conclusions have been ratified from the point of view of archaeometry, a different scientific discipline used in Archeology that applies physical and chemical analysis techniques to archaeological materials.

Specifically, the work analyzed samples of mortar from the monument; that is, the conglomerate that was used to prepare the different construction elements. The results made it possible to establish an indirect dating method confirming that Pompey's Curia did, in fact, feature several different construction phases.

The first of them, according to the results of the study, was during the time of Pompey himself, around 55 BC. The samples analyzed indicate that the monument also had a second phase of construction, which must have been around 19 BC, under Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Finally, a last stage of construction during the early medieval period has also been documented.

Tell me where you are from and I'll tell you when

The dating of these stages was established indirectly thanks to knowledge of the origins of the materials with which the monument was built. Analysis of the compositions of the samples analyzed allowed the authors, F. Marra, E. D´Ambrosio, M. Gaeta and A. Monterroso-Checa to ascertain the quarries from which they were extracted. The compositions and dates of removal from the quarries revealed that there were different chronological phases in the use of these construction materials.

All of this is evident because there is a clear distinction between the composition of the samples attributable to the first construction phase and those of the Augustan and medieval ones. For example, while in the initial stage of the monument's construction a material known as pink pozzolana, extracted from volcanic deposits in the interior of Rome, was exclusively used, in the samples linked to the second phase of construction volcanic glass is found, which is characteristic of a different kind ofpink pozzolanathat, due to the expansion of urban planning, was extracted from areas further away from the city's monumental center.

In this way, the work, published in the University of Oxford's prestigious journal Archaeometry, confirms, from a different perspective, the different construction phases of the building where Julius Caesar, one of history's most important politicians and soldiers, died, a fact pertinent not only to Archeology, but also to Roman History.

The study benefitted from collaboration with the Sovrintendenza Capitolina, the site's managing body, the University of Cordoba, the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology of Italy, and Sapienza University in Rome. It was financed by two projects: HAR 2011 25705 and HAR2013 41818P, under the Spanish Science & Innovation Ministry's National R&D Plan.

References

Marra, Fabrizio, D'Ambrosio, Ersilia, Gaeta, M. and Monterroso Checa, Antonio. (2021). Petrographical and geochemical criteriafor a chronology of Romanmortars between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD: the Curia of Pompey the Great. Archaeometry. 10.1111/arcm.12740.

Previous studies:

Monterroso, A., Martín, R., Murillo, J. I., y de los Ángeles Utrero, M. (2017). Curia Pompeia. Secuencia edilicia desde la Arqueología de la Arquitectura. Bullettino Della Commissione Archeologica Comunale Di Roma, 118, 55–84.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26598855